This is the second in a series of short articles on Arthur T. Polhill, whose correspondence and memoirs form a significant portion of the Polhill Collection.* For a short introduction to his life leading up to his decision to sail to China with the Cambridge Seven missionary band, in 1885,

see Introducing Rev. Arthur Twisleton Polhill, M.A, (1862-1935). There are several notable aspects of Arthur’s life that could be examined in more detail, but this essay will focus on the church or gospel hall (fú yīn táng, 福音堂) that Arthur built in Dazhou, Sichuan, in 1904.

On arrival in Shanghai, in March 1885, the Cambridge Seven were quite soon afterwards separated into two groups and sent to different parts of the country. Arthur, his brother Cecil and C. T. Studd took a boat up the Yangtse and Han Rivers, for there were no trains inland in those days, deep into the heart of China to the city of Hanzhong, in Shaanxi province.[1] Here they undertook language training as probationary missionaries and experienced the rigours of itinerant mission work in the surrounding cities, towns and villages. In 1888, Arthur relocated to Bazhong, Sichuan (巴中市, formerly Pacheo or Pachow), “a pretty little walled city,” to become the leader of his own station. In the same year, he married fellow missionary Alice Drake. They spent ten years together in the city, between 1888-1898.[2]

In 1899, they relocated to Dazhou (达州市, formerly known as Suiting, Suiting-fu, Suiding-fu and from the 1930s as Tahsien), "beautifully situated on the north side of the Ku [Zhou] River, a clear crystal stream," where they worked until the Boxer Uprising.[3] The Boxer Uprising was an indigenous uprising against foreign aggression in China, for the country had been humiliated by foreign powers for decades. The British, for example, twice went to war against the Chinese to assert their right to trade opium, a highly addictive and socially destructive narcotic. Missionaries were openly opposed to the opium trade, but extremely vulnerable to the anger of the subdued people. For example, the Cambridge Seven missionary, Montague Beauchamp, wrote to England in 1885, “Are you not surprised that any Chinaman will listen to the Gospel from an Englishman? I am sure I am.”[4]

Events began to unfold with Chinese paramilitary groups gathering at town boxing grounds (hence the Boxer Rebellion) or temples to vent their anger. Crowds would gather to watch them enact spiritual possession by characters from popular operas such as the Monkey King (Sun Wukong) or the God of War (Guangong).[5] They recruited young men and taught them trance-like rituals in order to initiate them for conflict. Some parts of China were also gripped by drought, and rumours began to spread that Christians had poisoned wells and supernaturally held back rain clouds. The dominance of some Chinese Catholic communities and their exemption from paying idol taxes served as another source of resentment. Chillingly, the Boxers killed around two hundred foreign missionaries and thousands of Chinese Christians until the Eight Nations Alliance defeated the joint Boxer-Chinese Imperial Army in 1900, after a tense fifty-five day standoff in Beijing (the subject of the 1963 epic 55 Days at Peking). It is still possible to see the marks on the large bronze cauldrons (once used for water in case of fire) in the Forbidden City, in Beijing, where it is said Alliance soldiers sharpened their bayonets (or so the tour guides say).

Scored cauldron in the Forbidden City, Beijing.

Foreigners in Sichuan province, where Arthur’s family were stationed, escaped much of the horror. He writes in his memoirs:

The Empress Dowager then telegraphed to the Governors throughout China: ‘The foreigners must be killed; even if the foreigners retire, they must still be killed.’ The wording of the telegram was allegedly altered by two friendly mandarins…‘sha’ [for] ‘kill’ being changed to ‘pao’ [for] ‘protect.’ The Yangtze Viceroys…also advised Governors and Viceroys to refrain from murdering foreigners…Yuan Shi Kai, Governor of Shantung, suppressed the Boxers in his province, and Yung Lu forbade the use of heavy artillery against the Legations in Peking. Providentially by these means the majority of the missionaries in inland China escaped.[6]

After a short break in England, Arthur and his family were able to return to Dazhou in 1902, where he spent the rest of his missionary career. One of the peaks of his time there was undoubtedly the completion of a large multi-purpose gospel hall. This led to the station becoming, in his opinion, “the most complete up to date station in the district if not the mission.”[7]

The idea for a new home and seven hundred seat church was borne out of Arthur’s unsatisfactory living conditions in Dazhou.[8] He wrote to the deputy director of the mission, Dixon Hoste, in August 1903, explaining that the house where his family lived was damp, too small, difficult to access and in an area surrounded by opium dens and brothels.[9] The building work started the following year, on 23 February 1904,[10] and by April it was well under way:

I am now watching the carpenters begin to erect the house. They are putting up 2 scaffoldings – before they begin – then the beams are put up and fitted together which will take place tomorrow. Already it…can be seen for miles around. Standing on a bit of hill – with nothing to hide it – save perhaps one or two trees near which give some grateful shade. The view is truly grand – so refreshing gazing at lovely mountains, trees and cottages.[11]

By August the complex was complete:

The Opening Day Aug 28 was just 6 months and 5 days from Feb 23 the day we started our boundary walls and 1 day under 6 months since the carpenters started work. Entering from the main street from East gate which runs by the river you turn up a passage some 20 yards - when you enter an ornamental gateway which is also conspicuous from the street itself - the first object that strikes you is the big church in front of you built in Chinese style with rounded top. The roadway passes on the L side next you ascend a flight of steps and pass a block of buildings containing the men’s guest halls on one side facing roadway on the other side facing the back - the women’s guest halls at the top of the roadway stands a round ornamental gateway leading into garden and dwelling house - this stands on the highest ground, and so gets a grand view on all four sides - the street below is hidden by trees and you look over on to the hills - on the N W side we see the city walls some 200 or 300 yards away. So it is a wonderful combination of country residence and yet proximity to crowded city.[12]

Photos of the church are scarce in the missionary periodicals and there are no labelled photos in the Polhill Collection, but Arthur was a keen amateur photographer and he did send photo of himself standing in front of a large building (see below).

An unlabelled photo in the Polhill Collection, Arthur can be seen on the right.

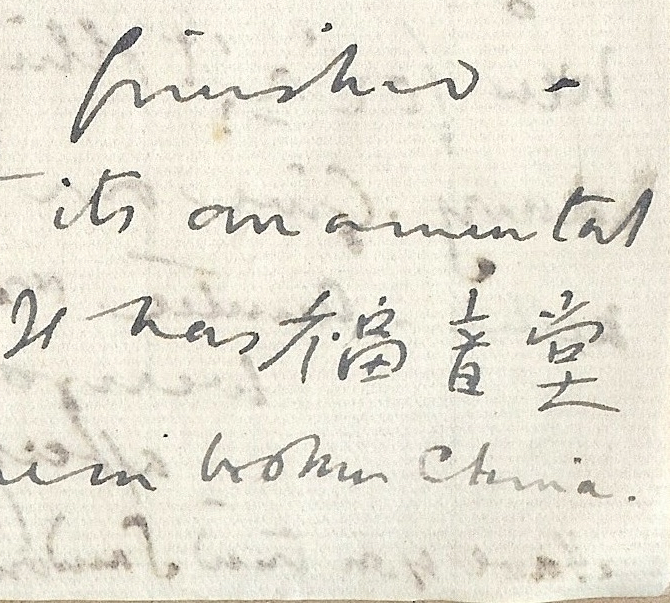

Notice the partially obscured writing above the doorway, this seems to confirm that it is indeed Arthur’s gospel hall for he wrote to his brother, in June 1904, shortly before the building work was complete, “it really looks finished – and pretty with its ornamental corners and top. It has 福音堂 [fúyīn tang – ‘gospel hall’] over the doorway done in broken China.”[13]

Chinese Characters from a letter between Arthur and his brother.

In the photo, the characters read from right to left.

Dazhou is now a large modern city of 6.5 million people. Could there be any remains of his Gospel Hall? Did it survive the Cultural Revolution? Arthur described its location as on the north side of the river, near the east gate of the city wall, and an online map search does locate a Dazhou City Gospel Hall in the Tong Chuan district which is on the north side of the river, and on the east side of the city. The physical building that Arthur erected is no longer there, instead the current church is located on the first floor of a modern building above a clinic, but it is pleasing to know that something remains of Arthur’s labours.

*NB: An extended version of this article was published as, "Beyond the Cambridge Seven: The Rev. Arthur Twistleton Polhill and the Dazhou Fú Yīn Táng" in Mission Round Table Vol.14 No.1 (Jan-Apr 2019), 16-23. Freely available online, click here.

For futher reading: The Humble Fragment Full of Hope and Glory: Subscriptions to the Shuting Church and Mission Hall.

The final essay in the series: Arthur Polhill's Photography and Social Reform.

[1] Montague Beauchamp joined them as far as Wuhan before returning to Shanghai and joining the other group. The two groups were initially stationed in neighboring provinces: Shaanxi and Shanxi. B. Broomhall (ed.) The Evangelisation of the World: A Missionary Band, A Record Consecration of Appeal 3rd ed. [EWMB] (London: Morgan & Scott, 1889), 24; A. Broomhall, Hudson Taylor and China’s Open Century Vol.6 (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1988), 374-5.

[2] A. Polhill, Memoirs, 52, PC [PC for Polhill Collection, PCO for Polhill Collection Online].

[3] A. Polhill, Memoirs, 70, PC.

[4] EWMB, 49.

[5] A. Austin, China’s Millions: The China Inland Mission and Late Qing Society (Cambridge: Eerdmans, 2007), 397.

[6] A. Polhill, Memoirs, 73, PC.

[7] A. Polhill to C. Polhill, 3 August 1904, PC.

[8] Arthur mentions the seating capacity to his brother in A. Polhill to C. Polhill, 18 July 1904, PC.

[9] Hoste subsequently forwarded the letter to his brother Cecil. A. Polhill to D. Hoste, 17 August 1903, PCO.

[10] Stated in a letter of the same date to his brother Cecil. A. Polhill to C. Polhill, 23 February 1904, PC.

[11] A. Polhill to C. Polhill, 4 April 1904, PC.

[12] A. Polhill to C. Polhill, 30 August 1904, PC.

[13] A. Polhill to C. Polhill, 10 June 1904, PC.