This is the final in a series of three short articles on Rev. Arthur T. Polhill, whose letters and memoirs form a significant portion of the Polhill Collection. For a short introduction to his life leading up to his decision to sail to China with the Cambridge Seven missionary band, in 1885, see Introducing Rev. Arthur Twisleton Polhill, M.A, (1862-1935).

Being a missionary could be extremely arduous work. In addition to Sunday services in his own church in Dazhou, Sichuan, Arthur made regular circular visits around an enormous parish, “You must remember,” he wrote to his brother in May 1904, “that I have a Wales or Scotland now to manage.”[1]His wife, Alice, frequently worried about the strain of the work on his health, “Arthur is working far beyond his strength,” she wrote in December 1904, “and is always tired he has so much to do he cannot do anything properly – I do not see how he can keep on. Much more could be done if only we had more helpers. Oh why do men wait at home for years, the open door may be shut them.”[2] It was imperative, therefore, for missionaries to find time to relax and engage in a pastime of some kind. This was not just for their own health but to help make the mission field an attractive option to prospective missionaries. Few would willingly come to the mission field if it meant certain burnout, illness and premature death. In his “Proposal for an Eton Mission to the East,” Arthur made an effort to make life in China sound tolerably comfortable:

Perhaps a few words about life in China…I recall what my fare has been today – curry for breakfast. Excellent soup, chicken and jam roll for lunch and equally suitable food for our evening meal. Other days we get according to the season: pheasants, deer, hares, wild fowl, beef, ducks, poultry. We keep our own cows and get milk cream and butter. We bake our own bread, cakes etc. while English vegetables are nearly all procurable here…The climate here is warm for 2 months of tropical heat – pleasant Spring and Autumn – with two months of Winter milder than at home…An English officer passing here surveying for railways, said in all his worlds travel, no scenery has come near the scenery around here, with its wooded mountains and rushing streams.[3]

Figure 1. Sichuan is famous for its scenery.

In the China Inland Mission’s “Instructions for Probationers,” missionaries were reminded they were in China to “Labour for God…to be a worker, not an idler,” but the advice went on, “…do not, however, think that the taking of regular exercise, sufficient to keep up your physical powers, will be a loss of time."[4] Arthur took the long view: lawn tennis[5] gardening[6] and anaerobic exercise[7] were all enjoyed by the Old Etonian at times, and it may be for this reason that he either outlived or remained in China for longer than many of his contemporaries.[8]

One of Arthur’s principal hobbies seems to have been amateur photography. The earliest mention of photography in the collection is on 5 December 1902, when Arthur wrote to his brother back in England, “Mr Row is getting me to instruct him in photography – at Shanghai. I started Mr Broumton off in photography – to get his mind off other things. So one’s little knowledge comes in useful to help others.”[9] Then just over a year later, in 25 January 1904, Arthur wrote to his brother again, “There is a new style of photo formatting called ‘Gum bichromate’ which seems likely to become a very popular method and yet simply acquired. I want [you] to go to the shop Swan & Edgar I think is the name in the High St. Bedford and see if it has the enclosed materials or could get there for me and send out by parcel post.”[10] From the following year, Arthur began regularly including small photographs in his correspondence.[11]

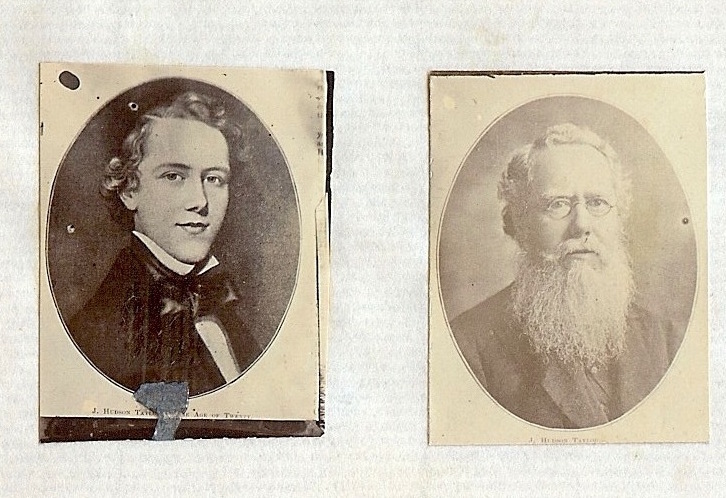

Figure 2. J. Hudson Taylor (the Founder and Director of the China Inland Mission): Young and Old

The first parcel-stamp sized images he sent were of the founder of the China Inland Mission J. Hudson Taylor (1832-1905). Two contrasting portraits are placed side-by-side in the letter head, the first of Taylor as a young man and the second as a much older man. It seems unlikely that Arthur took these photos himself, as he did not know Hudson Taylor when he was such a young man, but he may very well have developed them himself. The next image on the same letter is a photograph of Arthur’s mission station (the same photo appears on the inside cover of the Bulletin of the Diocese of Western China April 1910 cf. "Discovering Arthur Polhill's 福音堂, Fú Yīn Táng, Gospel Hall"). He does not appear to be in the photo, so it was almost certainly taken by him.

Figure 3. The Shuting [Dazhou] Mission Hall

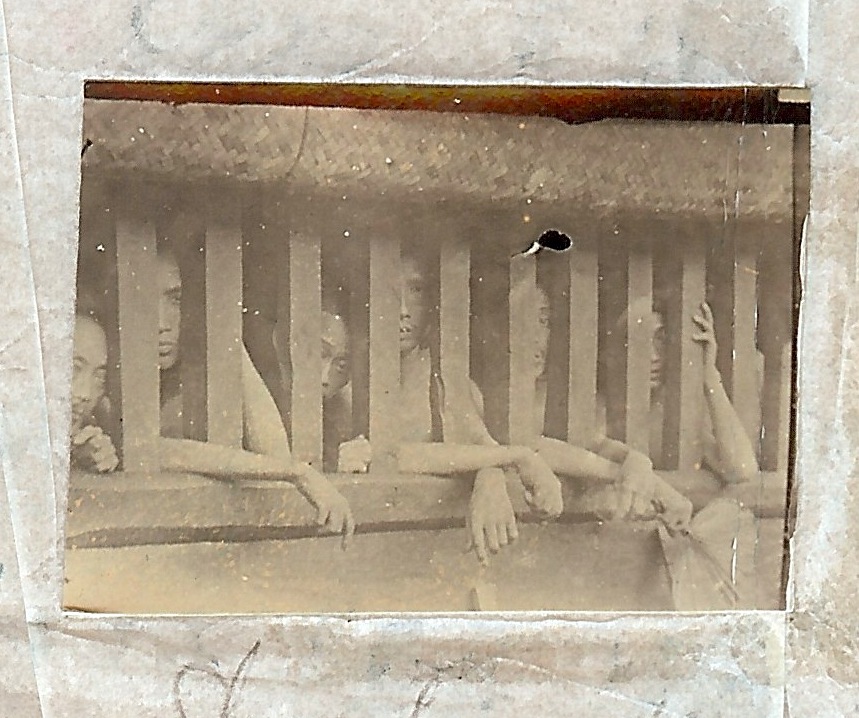

On 1 July 1905, Arthur’s photography comes to fruition in a long, eleven-page circular describing his work in and around Dázhōu (达州), Sìchuān (四川省).[12] The same two photos of Hudson Taylor, only larger, appear in the header of the circular, these are followed by a remarkable photograph of rather emaciated looking Chinese prisoners, with their arms protruding through a barred window.[13] Arthur writes:

Yesterday afternoon I went to visit the prisons [in Shuting i.e. Dázhōu] and found quite a number of the long-term prisoners had been liberated on the occasion of the Dowager Empress’ birthday not more than 10 out of 35 in that ward remaining though others had entered to take their place. The majority of prisoners are now in for highway robberies. This is owing to the scarcity of foodstuffs and famine prices on all foodstuffs. Numbers have died from the famine and now numbers are dying from famine fever which is the after effect. In some cases whole families are swept away by it and we hear many harrowing tales of woe.[14]

It reveals an important aspect of Arthur’s work. He was not just a missionary, he was also recording Chinese social history. The selling of family members and cannibalism were not unheard of to the missionaries.[15]

Figure 4. Chinese Prisoners in Dazhou, Sichuan (c.1905).

The next photograph is one of Arthur’s best. That of fellow missionary Dr William Wilson FRSA, taken mid-1905, showing him at work in his “science hall.”[17] It is an usually intimate photograph for the period, Wilson appears to be deep in concentration by his desk which is cluttered with instruments, medicine bottles and several sets of false teeth. Medical missionaries had to turn their hands to most things in the mission field, as professional dentists were extremely rare in rural China in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. His hair is in the traditional Chinese queue style and the contrast between east and west, ancient and modern is extremely striking. It is a glimpse of China at the threshold of modernity.

Figure 5. Dr William Wilson FRSA, in his Science Hall, Dazhou, Sichuan (c.1905).

During the long nineteenth century, missionaries found themselves wittingly and unwittingly part of the imperial ambitions of Western nations in China. They could be found holding views that would not be considered appropriate today, but there is no doubt that many did an enormous amount of good work. They brought metaphysical hope and faith, built hospitals and schools and introduced educational and technological advancements. In smaller ways, the simple disciplines of photography and writing exposed for analysis some of China’s social injustices. Arthur’s prison deputations were not just the activity of a “gentleman missionary,” but the source of serious social change. For example, he met with like-minded reformers (such as Alicia Little) to share his photos and discuss ideas, and his concerns for better conditions for the prisoners soon came to the attention of a young reformist Mandarin. Arthur writes in his memoirs:

My story must now pass to the arrival of the new mandarin, a young man of twenty-eight – tall, brisk, and full of life and vigour – with a brother studying in Japan. He is nicknamed Mr Chang-of-the-Strawshoes, because of his detective proclivities. He goes out of an evening in disguise to tea shops and opium dens, to know all that is going on, then has up bad characters to be punished…Mr. Chang called on me last week, and I returned his call to-day. He is a charming young fellow, and might almost have been a young Cambridge student, so free and unconventional, simply delighted with everything foreign…We talked over many things, prison reforms, street reforms, opium reforms, and so on. He fully approved of my suggestions – that prisons should be cleaner, lighter, and more sanitary, that prisoners should work, and not be kept idle all day, and taught a trade, or some way of making an honest livelihood. It is encouraging to me to hear him say he intends to build some model prisons.[18]

It is difficult to determine exactly how far Mandarin Chang followed through on his words, but Arthur used his position and his passion for photography to lobby for change and share progressive ideas. It is remarkable that Arthur and his camera had such a tremendous influence on the lives of so many people, both spiritually and practically.

For further reading see: Discovering Arthur Polhill’s 福音堂 (Fú Yīn Táng - Gospel Hall).

[1] Arthur Polhill to Cecil Polhill, 17 May 1904 in J. Usher ed. Polhill Collection Online (PCO), https://pconline.org.uk/browse/25-correspondence/family-correspondence/170-arthur-t-polhill-17-may-1904 (last accessed 23 September 2019).

[2] Alice Polhill to Cecil Polhill, 27 December 1904, PCO, https://pconline.org.uk/browse/25-correspondence/family-correspondence/82-alice-polhill-27-december-1904 (last accessed 23 September 2019).

[3] Arthur Polhill, “Proposal for an Eton Mission to the East (c.1903-04),” PCO, https://pconline.org.uk/browse/13-papers/281-proposal-for-eton-mission-to-the-east-arthur-polhill (last accessed 23 September 2019).

[4] William Cooper ed. The Book of Arrangements (June 1890), 29-30. My thanks to the David Hails, emeritus archivist for the Overseas Mission Fellowship, for sharing this document.

[5] Arthur Polhill to Cecil Polhill, 11 October 1904, PCO, https://pconline.org.uk/browse/25-correspondence/family-correspondence/176-arthur-t-polhill-11-october-1904 (last accessed 24 September 2019).

[6] Arthur Polhill to Cecil Polhill, 15 June 1904, PCO, https://pconline.org.uk/browse/25-correspondence/family-correspondence/172-arthur-t-polhill-15-june-1904 (24 September 2019).

[7] “I have been reading a remarkable book lent me by Parsons at Kweifu called Strength and How to Obtain It by Eugene Sandow…I am starting the exercises though I have no dumbbells.” Arthur Polhill to Cecil Polhill, 25 January 1904, PCO, https://pconline.org.uk/browse/25-correspondence/family-correspondence/165-arthur-t-polhill-25-january-1904 (24 September 2019).

[8] When Arthur retired in 1928, he had spent around forty years in China (when time on furlough is deducted). More time than C. T. Studd, Montague Beauchamp and his brother, Cecil; Roughly the same amount of time as Bishop Cassels; Only Dixon E. Hoste and (probably) Stanley P. Smith spent more time in China. Arthur died in 1935, outliving three of his Cambridge Seven colleagues: Bishop Cassels (d.1925), C. T. Studd (d.1931) and Stanley P. Smith (d.1931).

[9] Arthur Polhill to Cecil Polhill, 5 December 1902, PCO, https://pconline.org.uk/browse/25-correspondence/family-correspondence/159-arthur-t-polhill-5-december-1902

(25 September 2019).

[10] Arthur Polhill to Cecil Polhill, 25 January 1904, PCO, https://pconline.org.uk/browse/25-correspondence/family-correspondence/165-arthur-t-polhill-25-january-1904

(25 September 2019).

[11] Arthur Polhill to Cecil Polhill, 27 June 1905, in J. Usher ed. The Polhill Collection (PC).

[12] Arthur Polhill to Cecil Polhill, 1 July 1905, PC.

[13] Ibid, p3.

[14] Ibid, p6.

[15] Referring to a subsequent famine in 1936. The Bulletin of the Diocese of Western China (July 1936), p4. These can be viewed in the Cadbury Research Library (CRL), University of Birmingham, UK.

[16] Ibid, p4.

[17] The Bulletin of the Diocese of Western China (December 1907), CRL, p5.

[18] Such as the anti-foot binding and women’s rights activist Alicia Little (1845-1926), “Reform is in the air. Mr [Archibald] Mrs [Alicia] Little have just called in on their way up to Chung King and Chentu…she was interested in looking over my photos and told us about her work – anti-foot binding….” Arthur Polhill to Cecil Polhill, 30 January 1904, PCO, https://pconline.org.uk/browse/25-correspondence/family-correspondence/128-arthur-t-polhill-30-january-1904 (last accessed 25 September 2019) cf. Neil Connor and Ailin Tang “95-year-old woman in China speaks of the horrors of having bound feet” in The Telegraph (11 December 2015), https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/china/12046465/95-year-old-woman-in-China-speaks-of-the-horrors-of-having-bound-feet.html (last accessed 25 September 2019); Arthur Polhill, Two Etonians in China, 1885-1925, Reminiscences of Two of the “Cambridge Seven” Missionary Band (c. 1926 draft), PC, p95-6.

Photo credits: figure 1. from "msz010dzeta" on Pixabay (a royalty-free photo site), https://pixabay.com/photos/jiuzhaigou-lake-sichuan-china-2657789/ (last accessed 30 September 2019).