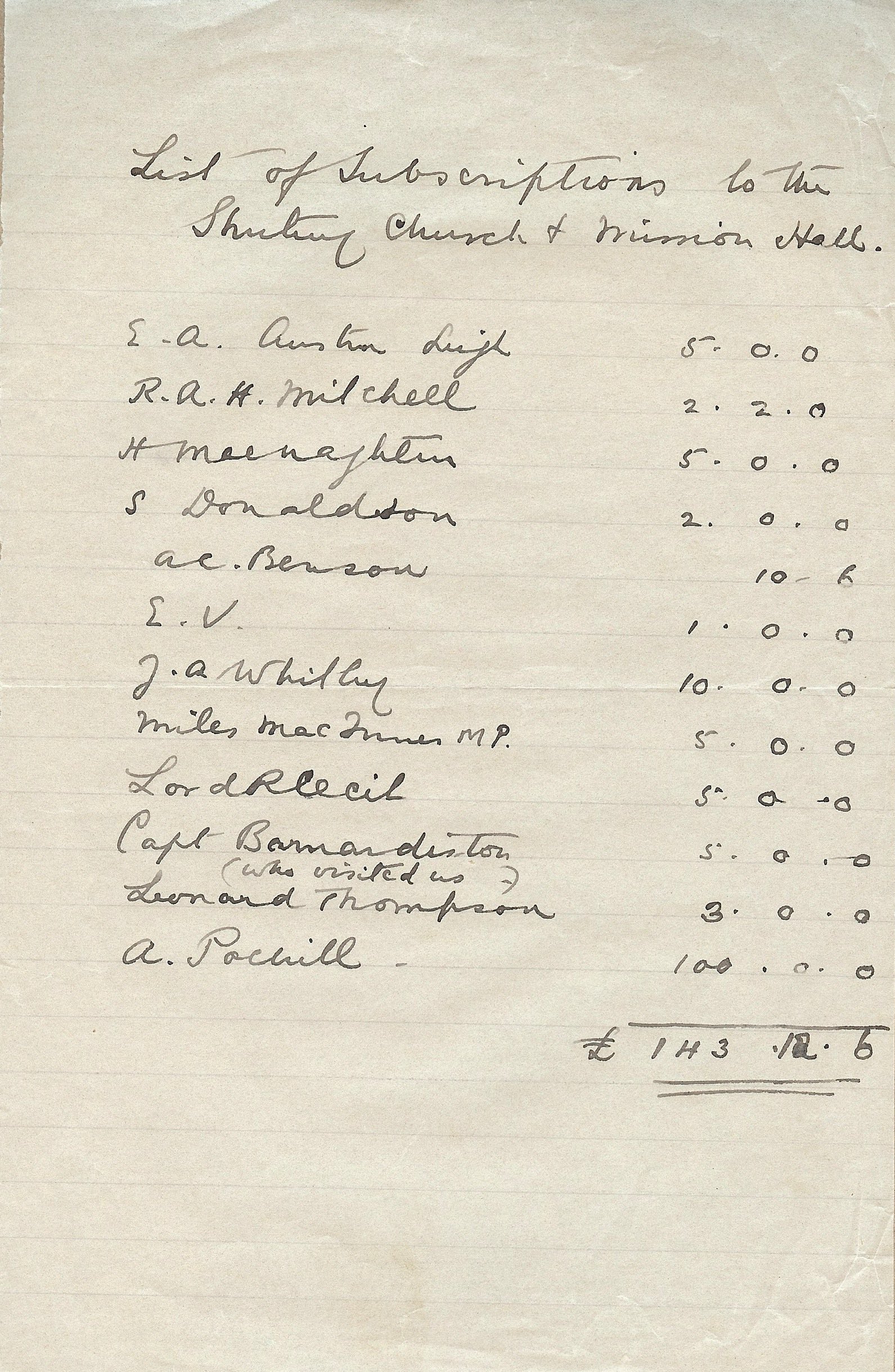

There is a small file of undated items and miscellaneous fragments in the Polhill Collection. One of the items is a short list of “subscriptions to the Shuting Church and Mission Hall.” Shuting is the former name for the city of Dazhou in central Sichuan, where Rev. Arthur Twistleton Polhill built a five hundred-seat

Gospel Hall in 1904 (see Discovering Arthur Polhill's 福音堂 Fú Yīn Táng - Gospel Hall). The list is very unassuming, written in Arthur’s hand, on a single sheet of writing paper but the people on the list are very interesting indeed.

List of Subscriptions to the Shuting Church and Mission Hall

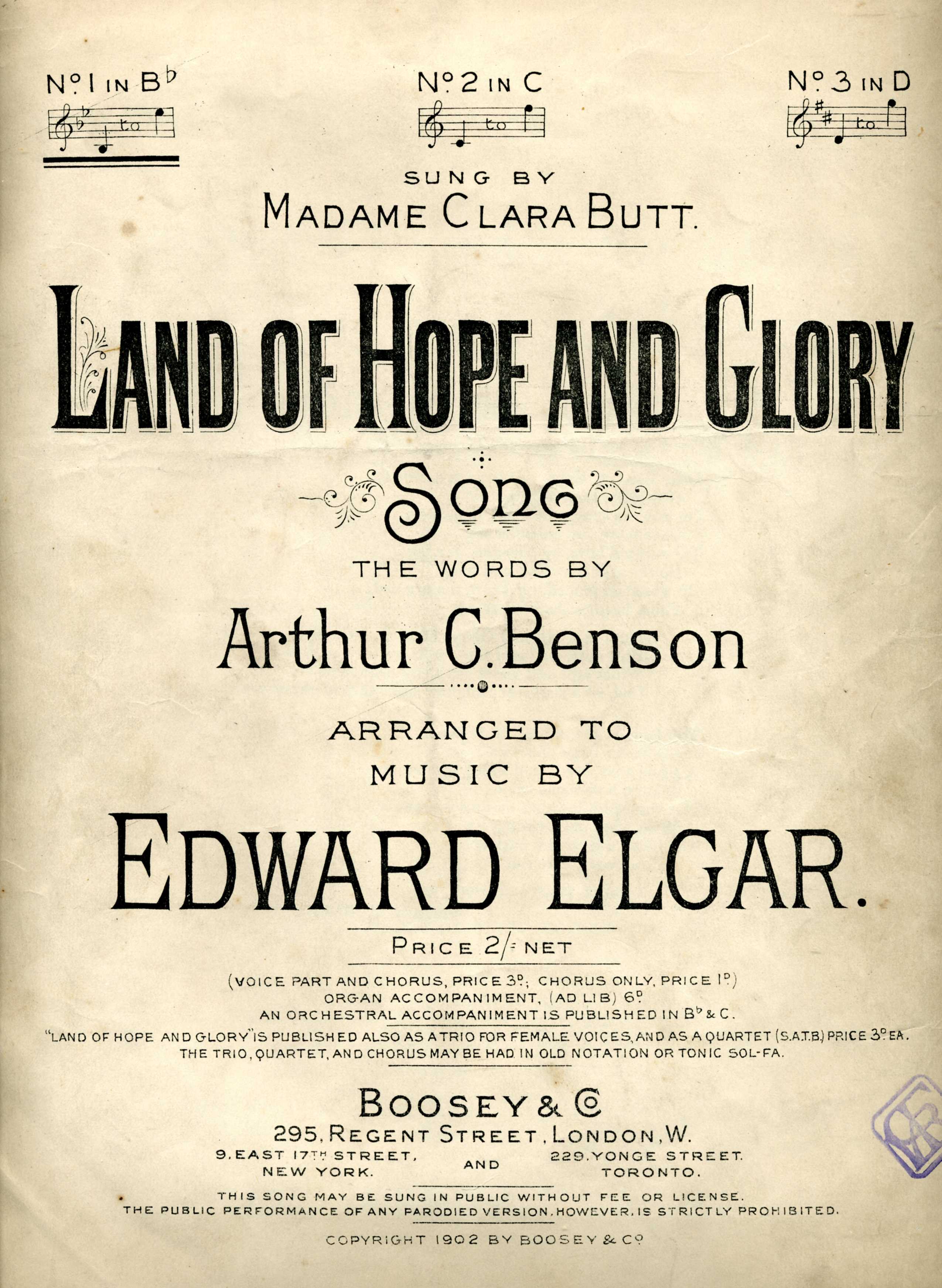

One of the most eminent entries on the list is that of A. C. Benson, almost certainly Arthur Christopher Benson (1862-1925), who was in the same year as Arthur Polhill at Eton. Benson was an outstanding scholar, essayist, poet, writer and Master at both Eton and Magdalene College Cambridge (having lectured at the latter on English Literature).[1] As master of the former he was regarded as, “one of the best ever known.” He is perhaps best-known today for writing the words to “Land of Hope and Glory,” used by Elgar in the composition of the same name. His father, The Reverend Canon Dr Edward White Benson, had been a cleric of the evangelical tradition, with a special interest in missionary work and about whom A. C. Benson had written a biography.[2] It may be this influence that led Benson to donate half a guinea (10/6 or 10 shillings and 6 pence) to Arthur’s gospel hall.

Sheet Music for Land of Hope and Glory

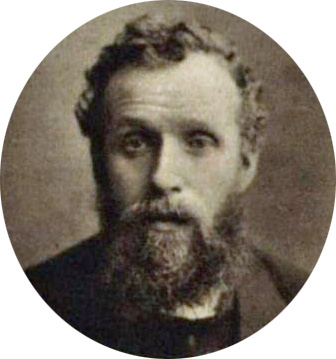

Another eminent entry is that of Lord R. Cecil. This probably refers to Lord Rupert Ernest William Gascoyne-Cecil (1863-1936), another old Eton friend who, like Arthur himself, became a cleric (Bishop of Exeter 1916-1936). His father, Lord Robert Cecil (1830-1903), was Conservative Prime Minister of the United Kingdom between 1895-1902. In this instance his affinity for Evangelicalism did not come from his father. Bebbington notes Lord Robert Cecil’s distaste for their “reign of rant…nasal accents of devout ejaculations,” and their, “incubus of narrow-mindedness…brooding over English society.”[3]

Lord Rupert, by contrast, actually credits Arthur Polhill in his book, Changing China, as inspiring him, “Our interest in China was first aroused by a letter from an old school-fellow, Arthur Polhill, who, with heroic self-denial, has spent the best part of his life in China as a missionary.”[4] Lord Rupert became the Chairman of the Committee of the “Eton in China” scheme, which aimed to open a school after the Eton model in China. Arthur seems to have been the leading inspiration for this project too, but sadly the Chinese Civil War thwarted development of the school and Arthur died before its conclusion. Exactly what happened to the scheme is beyond the scope of this article, but interestingly Eton does now offer online courses in China.

Lord Rupert (Bishop of Exeter)

There are, at least, four more Old Etonians on the subscription list. Hugh Macnaughton (d.1929) had also been a staff member at Eton during Arthur’s boyhood, latterly he held the post of Vice-Provost. Richard Arthur Henry “Mike” Mitchell (1843-1905) was a first-class cricketer, who supervised the Eton team from 1866. In this position he would have come to know Arthur, an accomplished sportsman, well. E. A. Austen Leigh probably refers to Edward Compton Austen Leigh, a lower master at Eton. There is a letter in the collection from him, dated August 1904, offering, “a mite to help you on.” Leigh wrote in the same letter rather prophetically, “The Japanese are a wonderful people but a missionary from the east predicted to us the other day that in a century’s time China and not Japan would be the nation in that quarter of the globe and a young Chinese student on the river bank asserted the same if they could only get the chance from their government that the Japanese have had.”[5] Rev. Stuart Alexander Donaldson was also an Eton master when Arthur was a school boy. He had, by 1904, moved onto become Master of Magdalene College, but he was a passionate advocate of overseas mission.[6] The Gospel Hall in Dazhou certainly has a fascinating pedigree.

The other names, excluding Arthur himself, remain something of a mystery.

[1] See “A Cambridge Alumni Database” s.v. “Benson, Arthur Christopher”: venn.lib.cam.ac.uk (last accessed June 2019).

[2] Venn, J. and Venn, J. A. ed. Alumni Cantabrigienses: A Biographical List of All Known Students, Graduates and Holders of Office at the University of Cambridge, From the Earliest Times to 1900. Volume 2: From 1752 to 1900; Part 1: Abbey-Challis (Cambridge: CUP, 1940), s.v. Benson, Edward White cf. D. Bebbington, Evangelicalism in Modern Britain: A History from the 1730s to the 1980s (London: Routledge, 1989), 140. Benson belonged to a party of Evangelical scholars thought to possess sufficient intellectual nous to offer a riposte to Essays and Reviews.

[3] Bebbington, 274. Salisbury had also refused to sell land for the erection of a Methodist chapel, Bebbington, 125.

[4] W. Gascoyne-Cecil, Changing China (London: James Nisbet & Co., 1911), iii. Freely available at the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/changingchina00gascuoft/page/n5

[5] Edward C. Austen Leigh to Cecil H. Polhill, 7 August 1904 in John M. Usher ed. The Polhill Collection Online: https://pconline.org.uk/browse/18-correspondence/domestic-correspondence/60-e-c-austin-leigh-7-august-1904 (last accessed June 2019). I assume, if this letter does refer to a donation to Arthur’s church, that Cecil was collecting these for Arthur. The church had already been built, however, so this may refer to a donation for something else.

[6] For example, he wrote, The Obligation of the Church to Foreign Mission Work Generally Among Non-Christian Peoples in 1908.