One of the largest sub-sections of the collection consists of approximately seventy letters from Arthur Polhill to his brother Cecil Polhill. This short essay is the first of a series of three essays designed to give a brief overview of his remarkable life. This is helpful for a number of reasons: firstly, it will help give some context to the correspondence between Arthur and Cecil;

secondly, it will give context to other items from Arthur in the collection, such as circulars and appeals and finally, it will serve as a useful preface for more detailed analyses of Arthur’s papers in future articles and essays.

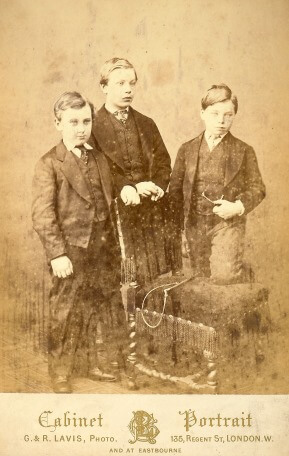

Arthur Twisleton Polhill-Turner was born on 7 February 1862, probably in Bedfordshire, to Captain Frederick Polhill-Turner MP and Emily Frances Polhill-Turner.[1] Emily’s family, the Page-Turner Barrons, were an enormously wealthy family, so according to custom Arthur's father Frederick adopted the Turner suffix to his own name becoming Frederick Polhill-Turner. Arthur was the youngest of the three Polhill brothers, but he was by about the age of ten the same height as his older brother Cecil (b.1860) and outgrew him as an adult. The two younger brothers seemed to share a close bond with one another that they did not have with their oldest brother Frederick (b.1858). For example, Cecil and Arthur became missionaries together, as did their only sister Alice. Later in life, the two younger brothers also co-wrote their memoirs together Two Etonians in China. Frederick, by contrast, inherited responsibility for the family estate in England but died when he was just thirty-three. He is never mentioned by the younger brothers in their memoirs. In 1902, the two surviving brothers, Arthur and Cecil, removed the “Turner” part of their name by deed poll, “to suit the times.”[2]

Arthur enjoyed sporting distinction at Eton and the University of Cambridge. At university he played football with the Old Etonians F.C, one of the best clubs in the country in those days. The Old Etonians won the All England Association Cup (latter known as the FA Cup) in 1878-79 and 1881-82. Arthur was not in the squad on those occasions, but he writes in his memoirs, “I had the pleasure of touring with them round the North of England and Scotland. Anderson, Kinnaird and Rawlinson, the Goalkeeper, were amongst the team. We beat Sheffield and Edinburgh University, but succumbed to the Glasgow Queen’s Park and Dumbarton.”[3] It is fair to conclude that professional football was in its infancy in those days, “I was amazed at the way the Scotch Backs used their heads to strike the ball in mid air. It was rather new to us Southerners.”[4]

Arthur’s life changed in 1882 when an unrefined North American Evangelist, Dwight L. Moody, was given the opportunity to address the nation’s elite at Cambridge. Arthur writes in his memoirs,

Mr D. L. Moody was a short thick-set man, with a broad American accent, and rather a dramatic manner, as he preached on Daniel, representing him as a man dressed in a frock coat, and carrying in his tail coat pocket a scroll and drawing it out with gusto, to the amusement of the Students, amounting to merriment…The last night…saw a wonderful change from the previous Sunday night; a crowded gathering, but so still you might hear a pin drop: a sense of awe and realization of the presence of God, no laughing or joking…the writer was drawn by the simple text Isaiah 12.2 and decided for Christ that night.[5]

The tradition in many wealthy families at that time was that the eldest son would inherit the family estate, the second son would join the military and the third son would become a Lawyer. The Polhill-Turners were no exception, but after Arthur’s conversion he writes of his transfer from law student to theology student, “The tone of the College was indeed greatly changed. The great Law College, now might be said to be ‘under grace’. The tide of revival continued to rise for the two following years, to the great delight of the principal of Ridley Hall, Rev. H. C. G. Moule, afterwards Bishop of Durham. I had transferred from Trinity Hall to Ridley Hall.”[6]

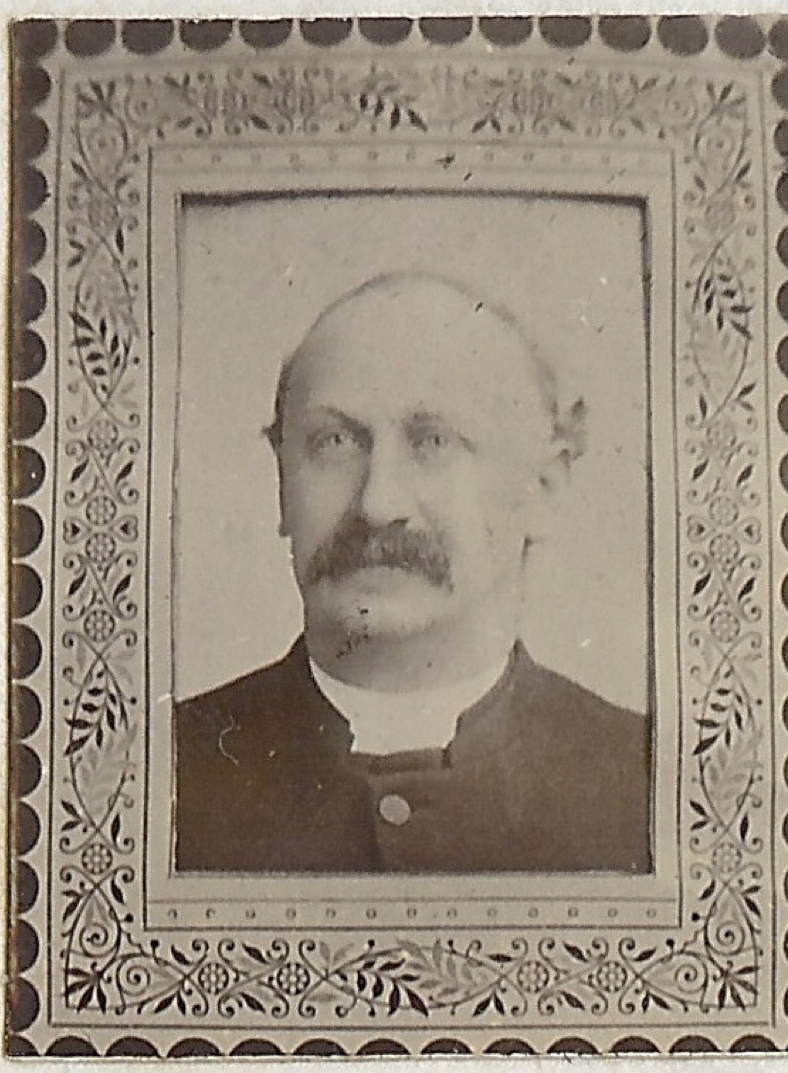

Exactly how and when Arthur decided to become an overseas missionary in China, rather than a parish vicar in England, is not clear. Broomhall and Pollock suggest the decision came after being given a copy of Hudson Taylor’s China’s Spiritual Need and Claims by fellow student Montague Beauchamp, probably sometime in 1882.[7] Yorkshireman J. Hudson Taylor (1832-1905) was a medical missionary to China and founded the China Inland Mission (CIM), in 1865, after having a vision of, “a million Chinese souls a month sweeping over into eternal darkness.”[8] In China’s Spiritual Need and Claims, Taylor condenses statistics into simple diagrams to illustrate how few missionaries and Christians there were for each of China’s enormous and densely populated provinces. By 1883, Taylor had returned to the UK to recruit new missionaries for the CIM. It is not unlikely that Arthur read Hudson Taylor’s work, but the principal of Ridley Hall, the evangelical Anglican Handley Moule, probably influenced Arthur too. For example, Moule’s two brothers, George Evans Moule (1828-1912) and Arthur Evans Moule (1836-1918), were already missionaries in China with the Anglican Church Missionary Society. This probably explains why Arthur had initially signed up to go to China with the Church Missionary Society before switching to the China Inland Mission in 1884.

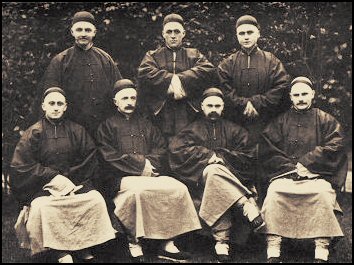

Arthur was the first of the so-called “Cambridge Seven” band to decide to become a missionary, probably as early as the winter of 1882-3. He was followed by Dixon Hoste (the only member of the seven not to have actually studied at the University of Cambridge) in July 1883; Stanley P. Smith, the son of a London surgeon, followed in March 1884; Smith then influenced the young Anglican curate William W. Cassels to join in October 1884; Smith also influenced the outstanding cricketer, named on ‘the Ashes’ trophy, C. T. Studd to join in November 1884 and this in turn influenced Montague Beauchamp, son of Sir Thomas William Brograve Proctor-Beauchamp, to join soon afterwards.[9] It is likely that Arthur switched from the CMS to the CIM after he observed his esteemed fellow students joining the CIM.

As for Arthur’s brother, Cecil, Arthur had been encouraging him to become an Evangelical Christian since his own conversion at the Moody campaign of 1882.[10] By January 1885, Cecil too had decided to join the China Inland Mission. The decision of seven fit, young, well-connected men (including a famous cricketer), giving up almost guaranteed lives of privilege and comfort in England for lives of itinerant mission work in rural China was quite the spectacle. They toured the nation’s universities and held rallies in large halls. The last of these on the eve of their departure for China, in the now-demolished Exeter Hall on the Strand, in London, had more than three thousand in attendance and was reported in The Times.[11] Arthur was just twenty-two when he left London, with his brother, and five compatriots for China on 5 February 1885. He would spend most of the next forty-three years of his life there.

Next essay in the series: Discovering Arthur Polhill's 福音堂 (Fú Yīn Táng - Gospel Hall).

[1] J. A. Venn, Alumni Cantabrigiensis: A Biographical List of All Known Students, Graduates and Holders of Office at the University of Cambridge, from the Earliest Times to 1900 (Cambridge: CUP, 1953). s, vv. ‘Polhill-Turner, Arthur Twisleton’

[2] A. Polhill, ‘Proposal for an Eton Mission to the East’ (c.1904), PC (Polhill Collection).

[3] A. Polhill, Memoirs, p4, PC.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid, p6.

[6] Ibid, p7.

[7] J. Pollock, The Cambridge Seven (Fearn: Christian Focus Publishing, 2006), 37 and A. Broomhall, Hudson Taylor and China’s Open Century Vol.6 (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1988), 334.

[8] A. Austin, China’s Millions: The China Inland Mission and Late Qing Society (Cambridge: Eerdmans, 2007), 181.

[9] Broomhall, 336-342.

[10] C. Polhill, Memoirs, 10, PCO (Polhill Colleciton Online).

[11] Pollock, 99-100.