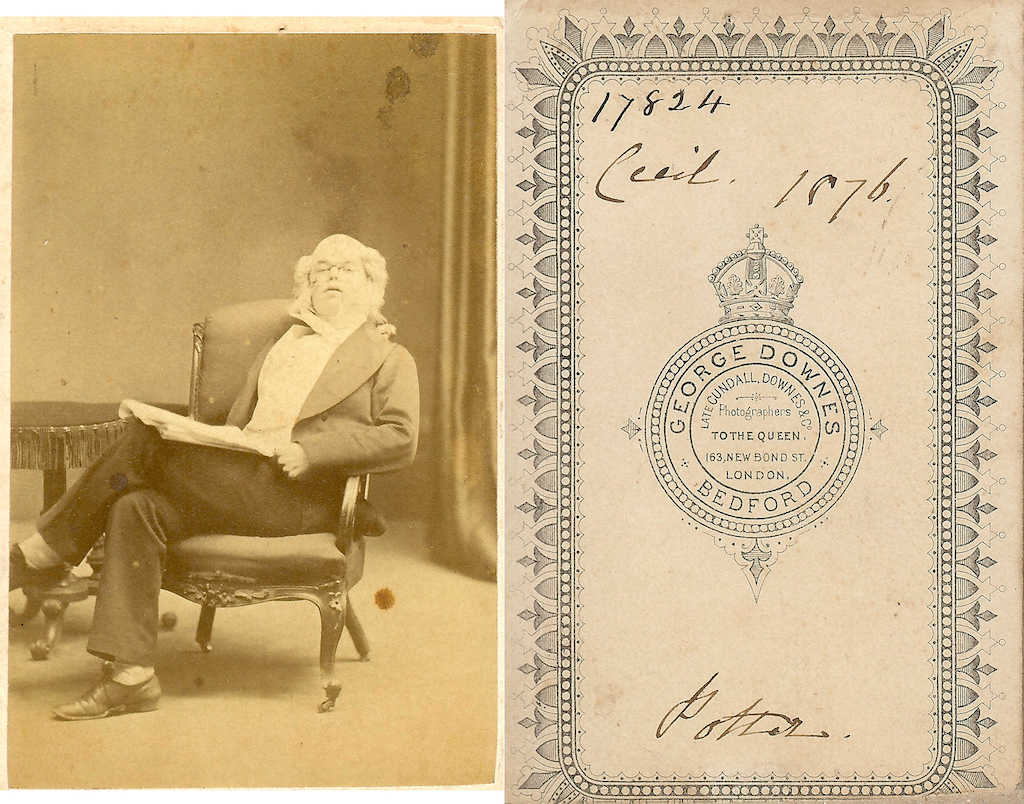

One of the most interesting items in the collection is a photograph of what appears to be an old man, but there's just something that's not quite right about it. The face doesn't seem to fit the bald crown and extravagantly white, bushy sideburns. On the back of the photo is says "Cecil 1876" and then further down "Potter." Could it be that this is actually a photograph of Cecil Polhill aged sixteen? Surprisingly enough, this is the most likely explanation.

Figure 1. Cecil in the Character of "Potter" (1876)

The Polhill family had a strong theatrical heritage. Cecil’s grandfather, Frederick Polhill (1798-1848), had owned the lease on the Royal Opera House and the Theatre Royal in London.[1] According to Sheppard, “One permanent feature of Polhill's tenancy remains—the colonnade in Russell Street, designed by Samuel Beazley and erected in 1831, not without some initial opposition from the committee of management of St. Paul's parish.”[2] The colonnade is indeed still there today. The Garrick Club, a gentlemen’s club for lovers of the Arts especially theatre, was also established in the Theatre Royal when Polhill was the lease holder.[3]

Figure 2. Collonade on Russell Street, London (Google Maps).

The family connection is not the only evidence that Cecil Polhill is almost certainly the ‘old man’ in the photograph. In the Winter of 1884, during a visit to his uncle in Germany, Polhill became an Evangelical Christian:

My next winter’s leave came, and I spent it at Stuttgart, studying German, living with a pleasant German family. My Uncle was British Resident at Stuttgart [to Charles I, King of Württemberg] and was very kind to me. Little did he know what was passing in my mind as together we went to the opera, and took long drives, but daily I pondered the Scriptures and thought, yes and prayed, so that when at last all good-byes were said, and I stepped into the railway carriage on my return to Aldershot, it was with a mind fully made up. I had yielded to and trusted in Jesus Christ as my Saviour, Lord and Master.[4]

Within a year he had settled on becoming an overseas missionary in China. He joined up with six other men connected to the University of Cambridge, known as the Cambridge Seven missionary band. One of Polhill’s fellow missionaries was a man called Charles Thomas “C. T.” Studd, who had been a member of the English national Cricket squad and was therefore a household name. His conversion and uptake of the missionary cause, along with six other athletic, well-educated young men caused quite a sensation in Victorian Britain, “never before, probably, in the history of missions,” according to The Nonconformist, “has so unique a band set out to labour in the foreign field as the one which stood last night on the platform of Exeter Hall; and rarely has more enthusiasm been evoked than was aroused by their appearance and their stirring words.”[5]

Figure 3. The Cambridge Seven Shortly After Arrival in Shanghai, 1885.

Back Row (L-R): C. T. Studd, Montagu Beauchamp, Stanley P. Smith.

Front Row (L-R): Arthur T. Polhill-Turner, Dixon E. Hoste, Cecil H. Polhill-Turner, Rev. William W. Cassels.

Some journalists hung on their every word. The record of their tour around the country and journey to China is well documented in Benjamin Broomhall’s The Evangelisation of the World: A Missionary Band. It ran into three editions and met with Queen Victoria’s approval.[6] After arriving in Shanghai, in March 1885, the Cambridge Seven spoke at the Lyceum theatre in Shanghai, where the following was recorded:

Mr Cecil Polhill-Turner [his full name until 1902] then addressed the meeting. He spoke of the joy of serving Christ. He could look up to Him constantly. He found no room for the world. He said he had played on boards like this (the theatre). He had tried everything that the world called pleasure, but nothing the world could offer could give peace and joy like the one now enjoyed.[7]

After his Evangelical conversion such frivolity had to be put to one side. Not because acting was necessarily sinful in and of itself, but because it was regarded as an unnecessary distraction from the real work of mission and evangelism. Times have of course changed, but it is a fascinating glimpse into the past of a man who led an incredible life.

Figure 4. A Young Cecil Henry Polhill Without Costume

If you enjoyed this article, you may also enjoy my book about Cecil Polhill:

Cecil Polhill: Missionary, Gentleman and Revivalist Vol.1 (1860-1914) (Leiden: Brill, 2020).

[1] For Royal Opera House: https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1820-1832/member/polhill-frederick-1798-1848; For Theatre Royal: https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol35/pp9-29

[2] https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol35/pp9-29

[3] John M. Usher, Cecil Polhill: Missionary, Gentleman and Revivalist Vol.1 (1860-1914) (Leiden: Brill, 2020), p.11.

[4] Cecil Polhill, “From Eton to China” in Two Etonians in China, 1885-1925 (1926 draft), p.11.

[5] The Nonconformist cited in Benjamin Broomhall, The Evangelisation of the World: A Missionary Band, A Record of Consecration and an Appeal 3rd Ed. (London: Morgan and Scott, 1889), p.3.

[6] C. Norman, A Flame of Sacred Love: The Life of Benjamin Broomhall 1829-1911, Friend of China: The Man Behind Hudson Taylor (Milton Keynes: Authentic, 1998), p.63.

[7] Usher, p.13.